Our region, the Eel River Valley of far-northern coastal California, was dotted with rural schools from the early 1880s to the 1960s. Above, a famed local activist and teacher, Miss Elizabeth Fulmor, and her class at Grant School (note to locals: not yet Grant Union) in 1911. This is an image of what the administration of William Howard Taft looked like (see relevance below).

WHEN MY SON WAS 12, talking and acting crazy, I pitched a fit about how wrong everything was that he was thinking and experiencing, and how the right way was exactly the path on which I had been guided.

In the middle of this righteous outburst, Ewing, my son’s stepfather, said, “Jesus Christ, Wendy! Leave him alone! The years between your childhood and his are the same as the years between your childhood and the administration of William Howard Taft.”

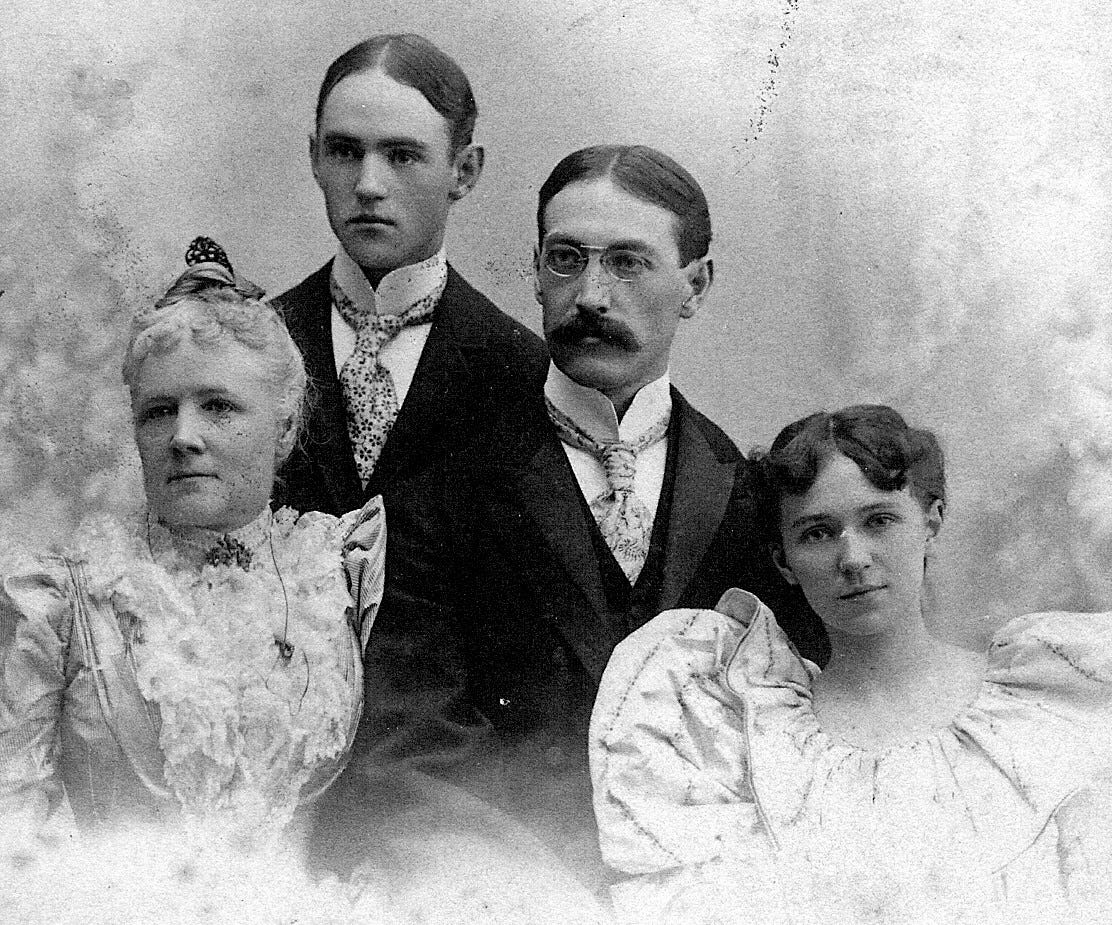

And between my grandchildren and me?1 Well, here’s a shot from 1885 that pretty well delineates the point. (This is an unidentified photo from the files of the Ferndale Museum2).

My family has four generations in the space that many people have seven or eight. My grandmother, Minna, was born in 1872; she had Mother Pewsitter when she was 40; I was born when my mother was 30; I had my son at 31. We tend to be late-bloomers, or as MP used to say, “Don’t worry about what people say about you: I never grew up, either.” I didn’t find that comforting.

Highly recommend joining the Ferndale Museum even —or especially—if you live elsewhere. The identifier “museum” is accurate for the physical plant, but the reality is that its overall program is astonishing proof of quantum physics’ theory of “time folding.” History is never viewed as a frozen past—it is, instead, a living commentary on current life. (“Yeah, his great-grandfather did the same thing, and we all know what happened to him.”)