Daddy Long Legs's jockey

A very long story about Ferndale, California's half-mile oval racetrack and the Fair, and a pioneer rider.

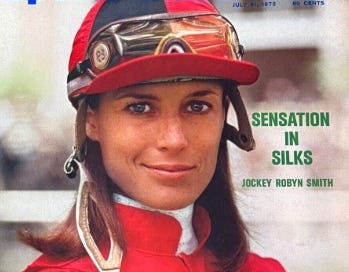

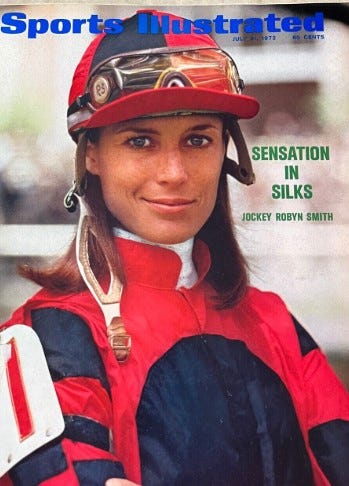

Above, Melody Dawn Robyn Miller Smith Astaire on the cover of a 1972 issue of Sports Illustrated. Below, the story I wrote about her several years ago for the Ferndale Museum. It’s a long piece, infused with my own passion for both thoroughbred racing and the little-known histories of women who just made. it. their. own. way. Amen.

SATURDAY, AUGUST 2, 1969 was the first day of the 1969 Humboldt County Fair. C. J. Hindley, the fair’s general manager, had a decade under his belt as successor to his father, and had, with the experience, the orneriness to keep traditions strong while embracing change. In the summer of ’69, C. J. was introducing a big change.

Riding under contract for Don Harmon, one of the most consistent and longtime owner/trainers at Ferndale’s challenging half-mile oval track (the final race on closing day is named in his memory, the Mademoiselle-Don Harmon Memorial), was a new jockey. This jockey, 5’7”, towered over the cohort. And this jockey was a woman.

C.J. and his court of racing aficionados from Ferndale and “out in the hills” had discovered her on their annual pilgrimage to the track at the Sonoma County Fair in Santa Rosa, a circuit meet that preceded the “Ferndale Fair” by three weeks.

“It was Hindley’s job to go to the back stretch and talk to the trainers, horse business,” recalled Dayton Titus, 94. “A whole bunch of us would go down with him to bet on the races and go out to dinner. We always went to a place called Lena’s, owned by the Bonfiglis, good old Italian people. One night, this guy and this gal come into Lena’s, talking about trying to get a [race horse] ride, and [the track officials] wouldn’t let her ride. Somebody said, ‘Maybe you could ride up in Ferndale,’ and I said, ‘If they won’t let her ride down here, they won’t let her ride up there.’ And then, I turned around and looked at her. Holy Christ. I said, ‘Oh, yeah, she can ride up there.’”

C.J. signed her up, and she rode the half-mile oval for the first time on the first day of the Fernddale meet, on a mount named, ironically, Charging Doe. And she got her first win.

The jockey’s name was Robyn Smith. She said she was born on August 14, 1944, in San Francisco, the daughter of a wealthy lumber baron. She’d spent part of her childhood in Hawaii, she said, and then she graduated from Stanford University in the class of ’66 with a degree in English after which she went under contract as a starlet at MGM Studios.

Not. In a 1977 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Smith told writer Irene Lacher, “I dissemble a bit, I like to say.”

That was the truth.

Regardless of the claims in her false narrative, Smith’s documented accomplishments earned her a place in horse racing history.

A year before she donned Harmon’s silks in Ferndale, Robyn Smith—perhaps a name she chose for her intended screen personality—was enrolled in the acting workshop at Columbia Studios in Los Angeles. She was dating a racehorse owner. One day, she accompanied him to the Santa Anita track in nearby Arcadia, where her boyfriend’s horse was being trained by Bruce Headley.

As she later recounted the events of that day, she had inside the rails and watched “…a girl galloping a horse and couldn’t believe my eyes. It never dawned on me women could be a part of racing.”

On the spot, she dissembled “a bit” to Headley about her experience with racehorses of which she had none and asked if he needed an exercise girl. He didn’t, he said, but her didn’t forget her. Almost a year later, he called Smith and offered her a job.

Assuming her proclaimed experience she was directed to begin exercising thoroughbreds at 6 a.m. the next day. (Novices start with stable ponies.)

“The horses weren’t scared, but boy, I was,” she later told writer Frank DeFord in an article for Sports Illustrated. “Thank god, it was dark those mornings and nobody really saw what I looked like on a horse.”

The horses ran away with her all the time, she recalled, and as time moved on, and the mornings got lighter, she couldn’t hide her lack of experience.

“You don’t gallop real good, do you?” Headley commented. Nevertheless, he kept her on. Determined to succeed, to be a star, Smith bought a book by Eddie Arcaro. (Arcaro, an American Thoroughbred Hall of Fame jockey who notched 4,779 wins before his death at 81 in 1997, is still the only rider to have won the U.S. Triple Crown twice). Smith studied and copied Arcaro’s style of sitting in the saddle, and of using the reins and the whip. During the exercising, she practiced breaking from the gate, leaning into turns, and “rating” (holding a horse back until the final burst to the finish line).

Smith’s fierce drive to succeed and the nature of the times were a lucky coincidence. A few months before her own application for a jockey’s license, in early 1969, Kathy Kusner, who had applied for a jockey’s license from the Maryland Racing Commission and was turned down, won a lawsuit under the nascent Civil Rights Act of 1968, securing the right for a female to be a licensed jockey.

“Girls had won the right to ride and [it] became something of a fad,” DeFord condescendingly wrote in Sports Illustrated. “Everyone had to see one once, like dirty movies.”

The track pioneers didn’t have it easy. When Penny Ann Early, the first female jockey to get a mount in the U.S., arrived at her first few races, the male jockeys boycotted the meet. Diane Crump, who took the honors of the first female to win a race (in February 1969), had to listen to fans shouting, “Go back to the kitchen! Make dinner!”

Robyn Smith’s first professional ride was April 3, 1969 at Golden Gate Fields near Berkeley. Kjell Qvale, an owner and a member of the board of GGF, thought a female jockey might be good for publicity. He agreed to let her ride Swift Yorky, from his stable, on Ladies’ Day at the track. Swift Yorky finished second and Smith received, according to the Associated Press, “a standing ovation…with a few boos.”

“All I want is a fair shot at some good mounts,” Smith told a reporter. “Some people won’t let me ride because I’m a girl but don’t worry, I’ll show them.”

She raced again at Golden Gate Fields, and then at Suffolk Downs in Boston and Exhibition Park in Toronto before coming to Ferndale.

Despite the Humboldt County Fair’s announcement of the novelty in the regional newspapers, Smith’s appearance didn’t generate large crowds at first. “It picked up over the course of the fair,” Dayton Titus recalled. “But she sure took off after that. She rode almost every one of the [Western Fair Association] tracks, and here, we had another woman shortly after. But Robyn Smith started it here, on the west coast.”

But Smith’s dreams were bigger than just one coast. She may have needed her invented biography to develop the confidence that fueled her success—but her real story, so shattered it’s difficult to reassemble, more dramatically underscores the difficulty of her journey.

Writing about Smith in the late 1970s (and without Smith’s cooperation), Lynn Haney, in a book titled The Lady is A Jock, says, “Any female jockey worth her stirrups is an odd duck. It requires so much grit and guts to swing a leg over a half-ton horse and ride against a pack of brusque little men that ordinary women…just don’t cut the mustard.”

Robyn Smith was born near Portland, Oregon in 1942, two years prior to her invented back story. She was the fifth child and third girl of Charles and Constance Miller. Her parents named her Melody. Shortly thereafter, Charles Miller, a cab driver, deserted the family, and Oregon Protective Services placed Melody/Robyn with the Orville Smith family in sparsely populated northeastern Morrow County.

“[The Smiths] had a shyster lawyer,” Constance Miller told writer Haney, “who put through these bogus adoption papers, and there was money exchanged between the Smiths and the Protective Society.” When Melody/Robyn was five, Constance filed a court action to have the adoption set aside. The request was denied by Morrow County courts, but was later upheld by the Oregon State Supreme Court, where Justice George Rossman ordered that Melody be returned to her mother, and then was placed in another home through the state foster care system via Catholic Charities, so as to keep her in the religious background of her family of origin. It was a landmark decision in Oregon law.

Living with her third set of parents, Frank and Hazel Kucero, Melody graduated from high school with the class of 1961, and, at 19, was no longer in the custody of the foster care system. Constance, living in Portland near her other young adult children, expected her “baby” to join them.

Melody had other plans. The Orville Smith family had moved to Seattle.

“Behind our backs, “ Constance said, “she called the Smiths because she knew they had money. I didn’t know a thing about it until a friend told me.”

When Constance confronted Melody about her decision, Melody said, “Go to hell, Mom!” One of Melody/Robyn’s brothers, Fred, said, “After I left home, I saw her once, on the street. I spoke to her, but she didn’t answer.”

“We’re not a close family,” Madalyn, one of her sisters, told author Haney.

FROM HER WIN IN FERNDALE, Robyn Smith headed for the big time on the east coast to the storied tracks of Aqueduct, Belmont Park, and Saratoga. In New York, it was even more difficult for her to get a race. Undeterred, she made the rounds of the barns, knocked on doors, and begged trainers for a chance to ride.

Finally, she got a break. “It was cold, driving rain,” trainer Frank Wright told Frank Deford for the Sports Illustrated story. “Robyn just stood there outside, with the rain falling on her, and when I looked down and saw the water running out of her boots, I said, ‘Well, please come inside.’ I told her, all right, I could give her a chance to gallop for me, and she just smiled and thanked me and ran right off to the next barn in the rain.”

Robyn raced for Wright on December 5, 1969 at Aqueduct in Queens. Her mount was Exotic Bird, a loser owned by a Detroit dentist. She finished fifth, in the middle of the pack. A few months later, she had her first New York win, also at Aqueduct, on Hill Cloud. Another owner, H. Allen Jerkens, “liked her interest. She [had] a lot of desire and as much determination as anyone I’ve ever been around.”

With Wright and now Jerkens in her corner, Robyn’s determination paid off. In 1970, she rode 34 mounts; in 1971, 350. (For perspective, jockey Bobby Woodhouse won his first race in 1969, too, and over the next two years, he had 1,657 mounts.)

“The lame excuse I always hear,” Robyn told Deford, is ‘I’d like to use you, Robyn, but my wife won’t let me.’”

Her presence on the New York tracks quickly attracted the attention of Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, Jr., whose father had died on the sinking of the Lusitania, and whose great-grandfather, William Henry Vanderbilt, had been (shipping and railroads) the richest man in the world. Vanderbilt was a racehorse owner who was also the youngest member of the prestigious Jockey Club, the president of Belmont Racetrack and Pimlico Race Course, and chairman of the board of the New York Racing Association.

By the spring of 1972, less than three years after she walked into Lena’s restaurant begging for a ride, she was riding for Vanderbilt.

“I wanted to see her make it,” Vanderbilt told Deford. “She deserves to make it. She’s just plain good, and she cares.”

The Vanderbilt connection was the key to the 1972 Sports Illustrated article—and her appearance on the magazine’s cover. “This young woman has risen from learning how to stay on a horse to a position among the elite in a very hard, dangerous profession,” Deford wrote. “…managed despite the strong bias against women in her field.”

Robyn tallied 44 wins in ’72.

On New Year’s Day, 1973, she raced Exciting Devorcee for Vanderbilt at Santa Anita. As she was preparing for the race, Vanderbilt came by with his friend, actor Fred Astaire. Astaire asked Robyn if she thought he should put money on her horse, and she replied that it was a bad idea. The filly was the long shot in the field. Astaire bet on her anyway, and Robyn and Exciting Devorcee won the race by a nose.

“I think Fred made about $10,000 that day,” Robyn told Barbara Walters years later in an NBC interview special. “I used to kid him and say, “Oh, you fell in love with me when I won that race!’”

The win set the tone for ’73. On March 1, she raced Vanderbilt’s North Sea at Aqueduct in the $27,450 Paumonok Handicap, the longest shot in a field of six. She broke third from the gate, but mastered the rating and overtook the leaders in the last furlong. The win (for which her take was $1, 647) was the first stakes race in history won by a female jockey.

The year was to be her busiest and most profitable. She rode 501 races, pulling in purses totaling $634,055; she was in the money one out of every three mounts, including 51 wins.

“Horses run freely for Robyn,” Vanderbilt said. “She has no fear on the track; she’s a fighter. As far as I know, this is the only girl in any sport who had ever competed with men on equal terms.”

And she still had a struggle getting mounts. In ’74, her numbers fell to 410 races; in ’75, only 256. Her winning percentage remained the same.

“All I ever get are long shots,” she told the New York Times. “The male jockeys get the Cadillacs and I get the Volkswagens, if I’m lucky. I mean, hell, I haven’t ridden for some of my old customers in months.”

Her career was slowing down, but on October 3, 1975, at Belmont Park, she had her best day. Wearing the cerise-and-white diamond silks of the Vanderbilt Stables, her first win of the day was on Lead Line. She won again on a Vanderbilt, Slink. And in the fifth race, she rode a Joseph Straus horse, Togs Drone, into the winner’s circle. She had her riding triple, and it was another first: a woman winning three victories in one afternoon on a major track.

In 1977, at the age of 35, she took a couple days off to film a commercial in Los Angeles for Shasta soft drinks. She called Fred Astaire, 78, and invited him to dinner.

“I thought, ‘A woman taking me out to dinner! What s this?’” Astaire later told the Chicago Tribune. “I’d never had a woman take me out to dinner. I got a kick out of it.”

“He came around and opened my door and he took my hand to help me out and something just happened. It was like bzzz,” Robyn told the Los Angeles Times.

A year later, she moved to California, to Arcadia, the home of Santa Anita, and convenient to Astaire’s home in Beverly Hills. Eighteen months later, during a live interview with Barbara Walters, they announced their wedding date. Robyn was 38 and Fred was 81. It was a longshot, but then, that was Robyn’s jam.

“Without getting maudlin,” she told Walters, “I’d never been loved in my life before. Ever. By anyone. It was meant to be. I had no control over it and neither did Fred.”

She retired from racing—Fred was concerned for her safety—and moved into the Beverly Hills mansion. Seven years later in 1987, Fred died. “Fred danced until a couple of weeks before he died,” Robyn said. “I’m not a great dancer, but anyone who dances with Fred becomes a great dancer.”

Robyn was 45 when Fred died. “I’m not one to sit home and eat potato chips and watch soap operas,” she said.

She became a pilot, first with helicopters, and then with jets. Her final career was as a corporate jet pilot.

She admitted the rush.

“I love that force, whether it’s out of the gate or in the air.”

Melody Dawn Robyn Miller Smith Astaire lives in the Bay Area; she’ll be 83 in August.

We’ll bet she still has a couple of furlongs to go.

A story read at racing pace. I was transfixed.

I ran into her a J&W Liquors in Ferndale when she was riding here. We had a brief conversation about the races and about Ferndale. I remember that she said she loved Ferndale.